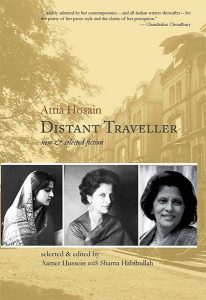

Attia Hosain: Unplugged

Rakhshanda Jalil reviews Distant Traveller: New and Selected Fiction, the late author’s latest publication

Some books cast a long shadow on their author’s oeuvre with the book becoming virtually synonymous with the writer’s name. Take, for instance, Arundhati Roy and The God of Small Things, Vladimir Nabokov and Lolita, Harper Lee and To Kill a Mockingbird or, for that matter, Attia Hosain and Sunlight on a Broken Column. Published in 1961, Attia Hosain’s (1913-1998) seminal book is remembered as much for the strength and beauty of her writing as for its depiction of a crumbling social order viewed through the prism of a modern, feminist, left-leaning sensibility. Regrettably, while Sunlight on a Broken Column is known to many as an iconic chronicle of the partition, little is known about Attia herself. With the book itself flitting in and out of print and Attia living abroad for the better part of her life, both have become a bit of an urban legend — talked about in literary circles with awe and admiration but seldom read and little known in any real sense.

Distant Traveller: New and Selected Fiction corrects an old wrong: it reintroduces Attia to a younger, fresher audience, one unburdened by the weight of expectations; what is more, it brings Attia out of the shadow of her one major work. As Ritu Menon writes in her Publisher’s Note: “The discovery of chapters of an unfinished novel and of short stories, written over a period of twenty-odd years (but none later than the mid-1970s), adds a new dimension to an oeuvre already remarkable for its range.” A previously unpublished essay, excerpts from an unfinished novel, 15 short stories (some of which have earlier appeared in the collection titled Phoenix Fled), a luminous Foreword by her daughter, Shama Habibullah, and a heart-warming Afterword by Aamer Hussein as well as hand-written pages from some of her unpublished manuscripts, make this a fitting tribute to Attia in her centenary year.

In revisiting Attia’s legacy, Distant Traveller not merely rediscovers her work for a new audience, it might, also, help find a new definition of feminism. In introducing us to a female tradition and a female voice that spoke without the table-thumping vigour of the bra-burning school of thought, it demonstrates how the very existence of self-awareness or the ability to take conscious decisions makes for empowered womanhood. At the same time, Attia’s writings compel us to re-examine the stereotyped notion that privilege precludes or excludes suffering or that someone born to privilege, like Attia was into a liberal taluqdar family, could not know suffering or exclusion. Her essay “Deep Roots” gives a glimpse of the losses that came in the wake of partition: “I am sad that I did not complete the books I have begun, or hoped to write, about the terrible pain when a country and a people are divided. It is never just a physical division, but a cutting apart of human beings.”

Explaining how she became a writer and why she chose to write in English and not in Urdu, her mother tongue, Attia writes: “Perhaps, subconsciously, to console myself for the maiming sense of loss of identity, I began to write. In this at least, I had the best of both my worlds.” On her choice of subjects she says: “The stories that I kept on writing in my head were always to do with the problems of human relationships, dilemmas in the context of social and political and philosophical conditions — problems I knew best, like my own breath, from my family’s eight hundred years in India.”

The home Attia had left behind in Lucknow and the new one she tried to make in London, where she worked for the BBC when her civil servant husband moved to Pakistan, finds a common ground in some of her writings. In No New Lands, No New Seas, raising a toast to Lucknow and its famous Toonda’s kababs while living among white folk, one of Attia’s characters speaks for Attia and her lost world: “…everyone knew you and you knew everyone and there was no need to explain. You were part of the whole and the whole could not be but that you were a part of it. Without explanation. Just being.” Muddled by neither lament nor nostalgia, it could well be a toast to Attia herself: a living testimonial to a whole, undivided India.