Come with me to the land of enchantment!

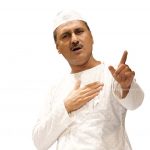

Mehru Jaffer on the delightfully dramatic, but dying art of the dastango

Lucknow is a city where fine speech is sown in its soil and sprinkled in its air. The tradition of the art of speaking is strong here. It is said that not a single citizen of the city at one time was left unspoiled by poetically inspired thoughts, similes and metaphors.

A good example of the unique way that the people of Lucknow lived and used language is best sought in the worthy, but dying art of dastangoi, or extempore story telling. This is a form of orally recited prose romance created, elaborated and transmitted by professional narrators, the stories told in Urdu have an immediate universal appeal.

The art was cultivated in royal courts in neighbouring Iran and it was the chief form of medieval Persian folk narrative. When Persian speakers came to India they did not forget to bring their stories with them. As Persian speaking rulers made northern India their home, raconteurs were encouraged to multiply and to practice their art of narration both privately before a single patron, and in public. Amongst numerous narratives in Urdu, The Adventures of Amir Hamza became more popular in India than even in Persia.

Over time countless Indian tales were added to Hamza’s Persian adventures and recited against the background of late 18th century Mughal India and the beauteous gardens of that time.

Naval Kishore

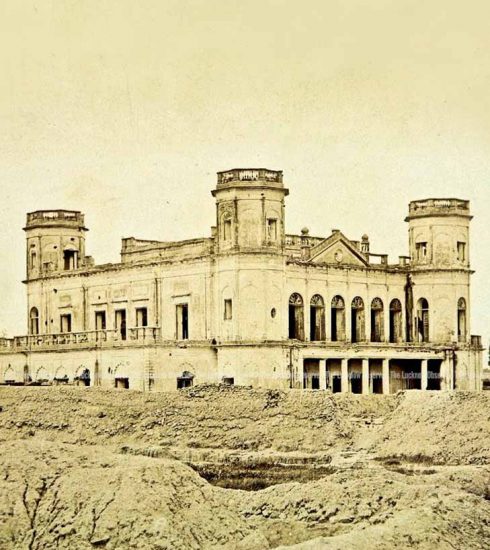

In 1858 Munshi Naval Kishore founded the famous Lucknow press and published the oral stories of Hamza’s adventures in Urdu. That publication is responsible for keeping alive this art form also in contemporary times.

The publications show the narrator use a rhythmic, repetitive almost hypnotic language to create a dreamlike world of marvel and enchantment where tigers prowl behind a curtain of mist and fish are found with their mouth full of pearls.

Lucknow contributed more stories to the Hamza adventures and which took several weeks of night long storytelling to complete. The last version published in 1917 in Lucknow is a massive 46 volume set, averaging 1000 pages each.

“Although originally a Persian production set in the Middle East, the Urdu version shows how far the story was reimagined into an Indian context in the course of many years of subcontinental retelling,” writes historian William Dalrymple in a review of The Adventures of Amir Hamza by Ghalib Lakhnavi and Abdullah Bilgrami, two of Urdu’s greatest prose writers from 19th century Lucknow whose work has been recently translated into English by Musharraf Ali Farooqi.

Tilism Hoshruba or the land of enchantment is the world’s first and longest magical fantasy to defy the laws of heaven and earth. Compiled by Muhammad Husain Jah and Ahmad Husain Qamar, it is one of the legends from the adventures of Hamza published in Urdu by the Naval Kishore press between 1893 and 1908.

In the English version by Farooqi, Jahcalls this particular legend the soul of adornment and epitome of grace in the realm of the written word, employing proper idioms and chaste expression of the Urdu language to convert devotees of the beloved lore to its marvelous charms.

Jah compares a meadow in the tale to one more delightful than the Garden of Eden and where flowers shine like jewels on the green expanse.

The lustrous dew was as pearls bonded with the emerald of grass. Every where there was a profusion of many coloured flowers for parsangs on end the fragrance of the flowers reached. In the same garden the girls are as coquettish, beautiful and lovely as the moon and as stately as the sun in the heavens.

They are between the ages of fifteen and sixteen years and familiar with the pangs of adolescence and nights of desire. Among them is a princess whose beauty is the envy of the moon.

Lucknow narratives

Even before the adventures of Hamza made it to Lucknow folk narratives were recited routinely in the city. Stories about everyday life circulated orally in some form or the other. Prose had always existed here and romantic fairy tales and heroic legends were seldom lacking in popular imagination. Over time the existing folk legends about demons, god men and half human half animal creatures intertwined into the narration of Hamza till the stories were neither Hindu nor Muslim but loved by everyone interested in worlds that exist beyond the world of humans.

From the bedside of the monarch when the same love of lore had whispered down into the marketplace it did not fail to dazzle the imagination of people on the pavement too, inspiring the vegetable vendor to converse in verse and to hawk his ware poetically: Crisp as Majnu’s ribs, and slender as Laila’s finger promises this singer, is the day’s cucumber. Buy, buy it here.

Persian stories were enjoyed by the Persianised northern Indian elite for centuries. The beauty of Urdu was that it bridged the gap between the Persian speaking elite and the people they ruled. Born in the barracks of Persian speaking Turkic warriors who made Delhi their capital city in the 12th century, Urdu initially was just a collection of words borrowed from local dialects and Persian.

By the 18th century Urdu matured into a literary language and it is easy to imagine an oral folk narrative tradition with simple Urdu tales told in the bazaar.

Author Annemarie Schimmel suspects that the story of Hamza, son of Abdul Muttalib, real life hero from history and paternal uncle of Muhammad, the Prophet was probably introduced to the Indian subcontinent in the 11th century from the time of Mahmud Ghazni, the Persian speaking Turkic warrior who commissioned Ferdausi, the Persian poet to scribe the Shahnama, the inspiration for the Hamzanama, or the adventures of Hamza.

Delhi

Professional Urdu story narration became popular in Delhi around 1830. As the influence of Persian declined, it was the Urdu tales that reigned supreme in North India not just for the story but for the utterly mesmerising style of narration.

By the time the art of dastangoi made it to Lucknow in the 19th century the stage was set for narrators who dressed in loose robes of fine muslin embroidered in lattice work. The button had just been introduced to India from Europe. In Lucknow a waistcoat up to the neck became a fashion with buttons running down in the front. They may have also worn matching skull caps and squatted on expensive carpets spread out on the floor under a canopy of a midnight blue sky, lit up by stars and huddling in a circle of shadows thrown up by their own, flickering soul.

The tales continued in winter time when the air was thick with the smell of the rambling rose mingled with smoke from fires lit in sandal wood. In high summer it was the aroma of the plump jasmine blossoms that kept the city in high spirits and helped audiences to fuel their fantasy to keep pace with that of the story teller.At some point every community had its own story teller who was invited to assemblies attended by audiences dressed in their best, puffing at water pipes and chewing betel leaves that made the rounds at the expense of a wealthy host. Opium flavoured drinks surely were the secret that turned the real world of the listener into enchantment and the world of illusion into reality.

The Hamza stories in Urdu are a mixture of Hindu and Muslim tales, inspired by Avadh’s all inclusive ganga-jamuni tehzeeb or way of life that is inspired by the elegant confluence of the glorious waters of the Ganga and Jamuna rivers.

The dastans are yours as much as they are mine and as precious as the vanished gold and pearls from the same river bed. Even if it is only in memory of the good old times of an Indo Islamic world at its best, we must once again lend a ear to the barely audible sotto voce of the dastango.