Dasht-e-Junoon

The Missing Manuscript

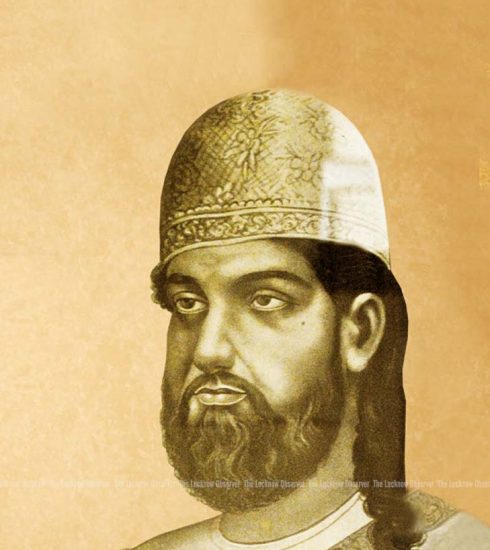

Shah Iqbal Ahmed Sabri Quddusi was a descendant of the Sufi saints. His paternal ancestors, including his father Shah Masood Ahmed Sabri, were sajjada nashins of the dargah of Ali Ahmed Sabir of Kaliyar Sharif. Through his mother, he traced his lineage from Shaikh Ahmed Abdul Haq, Rudauli’s patron saint. Born in Rudauli around 1935, he lost his mother soon after the birth of his brother Shah Akhlaq Ahmed, two years junior to him. When Iqbal turned seven, the brothers also lost their father, who was murdered while distributing alms one night at the Kaliyar Sharif Dargah. It was a trying time and his maternal grandfather Shah Hayat Ahmed brought his young grandsons to Rudauli. They grew up surrounded by doting relatives. Having lost both parents, they became the focus of the entire clan especially their maternal grandparents and their mother’s siblings.

The brothers were born into an atmosphere steeped in mysticism and poetry. They were especially close to their maternal grandfather, a Sufi poet and sajjada nashin of the dargah of Ahmed Abdul Haq. Their uncle, Shah Afaq Ahmed, the next sajjada nashin, played a major role in their intellectual growth. He introduced them to the leading lights of Urdu and Sufi poetry. The annual urs at Rudauli dargah was noted, among other special features, for the high quality of its qawali mahfils. Apart from the sajjadas of other dargahs, scholars, especially the Farangi Mahalis, Maulana Hasrat Mohani and literary figures, include poets like Jigar Muradabadi too came Rudauli to attend the Urs. Khumar Barabankavi, a young poet then, was a frequent guest at the family khanqah. Mushairas were a regular feature of Rudauli life. Some of Iqbal’s elders were acclaimed poets, like his cousin, Shah Mobin Ahmed (Manzar Rudaulavi).

Such was the background in which the two brothers grew up. In the introduction to his unpublished divan ìDasht e Junoonî, Iqbal mentions that he commenced writing poetry in the early 1950s, and this took centre stage in his life, becoming his junoon. He started participating in local mushairas and getting acclaim for his ghazals, some of which were published in prestigious journals including Kitabnuma (Delhi), Naya Daur (Lucknow) and Muarif (Azamgarh). Apart from poetry, his articles on the work of poets including Asar Lucknowi began to appear in local journals. He regularly participated in the organisation of literary activities in Rudauli, especially Yaum e Majaz. Iqbal was also in contact with several leading poets, including Khumar Barabankvi, Bakar Mehdi and Sharib Rudaulavi. He rarely left Rudauli, but regularly corresponded with friends and relatives, often enclosing his new ghazals. Iqbal’s poetry reflected the influence of old masters, especially Meer Taqi Meer, his favourite poet.

It was an enriching life in Rudauli during the 1950s and 60s. On summer evenings, dressed in a snow-white kurta, young Iqbal stopped briefly for fateha at the shady dargah and headed towards Tipai (area in Rudauli) to meet up with lifelong friends Javed, Omar and Shibli. They gathered at the little teashop, sharing poetry and discussing current affairs and their readings of the day. The only reminder of the passing time was the old bronze gong on Babu Mian’s spacious terrace, which was dutifully struck every hour. Around dusk they would all return home. Playing baitbazi was a favourite after-dinner pastime, in which family members participated. It was a frugal and simple life, minus telephones and televisions. Needs were few, and people enjoyed spending their time with each other.

Years went by. Iqbal Mian; as he was referred to by everyone, became an icon of Rudauli’s Ganga-Jamni culture. An embodiment of refinement, moderation, honesty and sincerity, slowly and surely, he became Rudauli’s chief resident poet. Like several of his friends, he had remained a bachelor, devoting his time and energy to literary pursuits. Perhaps the joint family system and his closeness to his brother’s children made up for that. Iqbal played a major role in passing on the passion for poetry to the younger generations of his extended family, especially to his nieces Saira, Shaista and Mony. By the 1990s, friends and family members started suggesting that he publish his divan, a collection of his poetry. Being modest and self-effacing, he was not sure if it was worthwhile to do so. In a letter addressed to a cousin, he mentioned his reluctance, stating, ìPublishing a divan is no child’s playî. However, he prepared a manuscript and sent it to Professor Aftab Ahmed Siddiqui, a relative and professor of Urdu at the University of Karachi. The renowned professor had agreed to write the preface to the book. He sent the manuscript back to Iqbal for correction of some typographical errors. Unfortunately, soon after that, Professor Aftab passed away peacefully in his home in Karachi. Iqbal then requested a friend and fellow poet to write the preface. He also prepared a five-page introduction and an autobiographical essay, which were to be included in his collected works.

As the new millennium was dawning, much had changed. Many of Iqbal’s friends and elders had passed away. He had moved out of the khanqah to another part of his ancestral home.

His papers, books, letters and albums were still in boxes and trunks when his health began to fail. Work on his divan had to be set aside. In spite of the insistence of his doctor in Rudauli, he did not go to Lucknow for investigation. He had seemed to be improving, when suddenly he developed severe chest pain. He was taken to a hospital in Lucknow where he died a few hours later, in May 2004.

Despite searching everywhere possible, Iqbal’s nephew Shah Masood Ghazali has not been able to locate his manuscript. All that remains is the five-page autobiographical introduction Harf e Aghaz for his unpublished book, which he had entitled Dasht e Junoon. What is also accessible is a video of Iqbal Rudaulavi reciting his poetry, uploaded on youtube by his cousin Mahmood Jamal. It brings back memories of him sitting in the verandah, which encircled his ancestral khanqah, observing the world going by. Sunlight filters through the sprawling branches of the old pakaria tree onto the shimmering roof of the adjacent mausoleum. The smell of parched earth beneath the first monsoon showers soothes the senses. Ancestral voices echo through the empty hall behind him. Qawwali music lingers on in the spacious courtyard. Good spirits and resident jinns guard the ancient abode without manifesting their presence. The mood of the poet and his surroundings varies as day progresses into night. And he writes:

“Hai agar che ghair mumkin magar aarzoo yehi hai

Koi kash aisa aaye wahi bazm phir sajae”

Farida Jamal, Kuala Lumpur

(Published in The Lucknow Observer, Volume 2 Issue 19, 5th October 2015)