Here is to you Zohra Sehgal!

Zohra Sehgal died at the age of 102 years last month. She was one of the first Indian actresses to achieve a truly international profile, with roles in films like Bend It Like Beckham in 2002 and Bhaji on the Beach in 1993.

Typically in her later years she played the part of a traditional south Asian woman struggling to come to terms with the pressures of living in a modern, alien culture as her children and grandchildren increasingly abandon the old ways.

She also appeared in a number of TV series, including The Jewel in the Crown in 1984 and Dr Who in 1964-65), and her Bollywood output was prolific well into her 90s.

Zohra arrived in the UK in 1962, to take up a British Drama League scholarship. After working as a dresser at the Old Vic and playing bit parts in the theatre, she became the face of the BBC’s early attempts at multiculturalism, presenting programmes aimed at new migrants and appearing in the 1977 serial Padosi or neighbours. This led to roles in Courtesans of Bombay in 1983, a docudrama directed by Ismail Merchant, but it was The Jewel in the Crown that brought her wider recognition, and made her a reliable feature of many subsequent British Asian productions, including Channel 4’s first Asian comedy series, Tandoori Nights in 1985-87. She was in her 80s by the time she moved back to India, but went on to appear in a string of films, culminating in Cheeni Kum in 2007, in which she played the mother of the Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan.

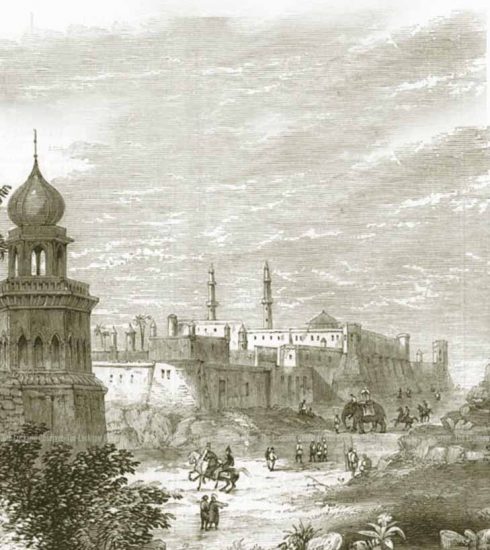

She defied expectations throughout her life: a career in show business was not the conventional choice for a girl from an aristocratic Muslim family in Saharanpur, northern India. Born Sahibzadi Zohra Begum Mumtaz-ullah Khan, she was one of seven siblings; her mother died when she was young and her father rather spoiled her. She first encountered art and culture at Queen Mary College, Lahore, where strict British schoolmistresses educated the daughters of the Indian upper classes.

Having resolved to become a dancer and actor, she managed to get to Germany in 1933, where she studied under the dance pioneer Mary Wigman. She later toured several countries with the dancer Uday Shankar, elder brother of Ravi Shankar, who was then a small-part dancer in his company.

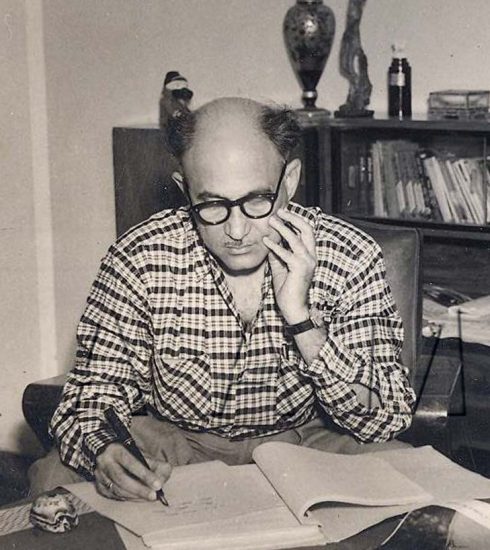

She met her husband, the painter Kameshwar Sehgal, in an arts centre founded by Uday Shankar in the Himalayan foothills. Again, it was an unconventional choice: Kameshwar was eight years younger than Zohra and he was a Hindu. They married, in the face of considerable

opposition, in 1942.

The couple started a dance school in Lahore, but tensions over their marriage forced them to move to Bombay, which was then a comparatively liberal city. They joined the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), which consisted of progressive and secular intellectuals, poets, writers, film-makers, actors and artists. Most of the country’s leftwing luminaries were active IPTA members.

In 1946, Zohra appeared in Dharti Ke Lal, a film about the Bengal famine of 1943 that formed part of a new wave of socially engaged Indian cinema. The same year, she featured in Neecha Nagar, a groundbreaking social realist film, Indian cinema’s first international critical success and winner of the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. The atmospheric soundtrack of both films was provided by Ravi Shankar.

After partition in 1947, Zohra, as a leading lady of Prithvi Theatre founded by Prithviraj Kapoor, toured the country performing plays advocating communal harmony. In 1959, tragedy struck when Kameshwar took his own life, leaving her to bring up their two young children.

Three years later, she took up the British Drama League scholarship and they went to London.

It may have been her regular yoga exercises and absolute discipline in matters of eating and sleeping that gave Sehgal the energy of a woman less than half her age. Asked in early 2013 what she had enjoyed most in life, her eyes lit up. “Sex! Sex! And more sex!” she declared.

India’s National Academy of Music, Dance and Drama made her a fellow in 2004, and she was honoured with the country’s high Padma Vibhushan title in 2010. She is survived by her dancer- choreographer daughter, Kiran, her son, Pavan, four grandchildren and a great granddaughter.