Making up stories!

Just like our very own desi dastango Mahmood Farooqi, Richard Hamilton is trying to rescue the art of oral storytelling by writing a book on story tellers in Morocco. In an exclusive interview with The Lucknow Observer Hamilton warns that when a story teller dies it is like a library is burnt.

When did you get hooked to storytelling?

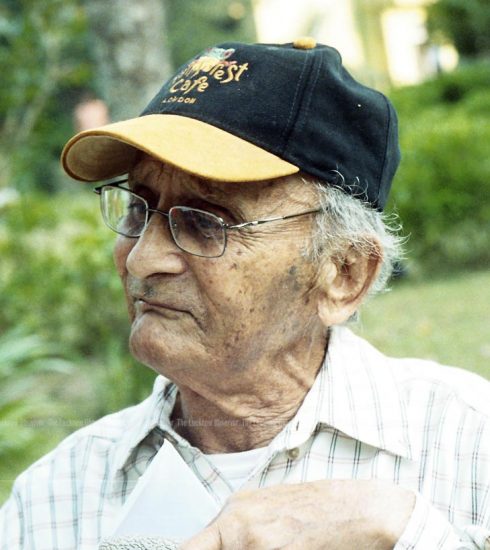

In 2006 I was working for the BBC as their correspondent in Morocco. I was based in Rabat but I travelled across the region, and fell in love with it. Towards the end of the year I decided to work on a radio feature for the BBC World Service about the few surviving storytellers of Marrakech, or hlaykia as they are called in Morocco. At the time I did not know very much about Moroccan storytelling; only that it was an ancient tradition and that it was under threat. I sat down with one particular hlayki. His name was Moulay Mohamed El Jabri and he was 72 years old. I distinctly remember it was one of those bright clear winter days in Marrakech when you could

see the snow on the peaks of the Atlas mountains. I sat down with him and a translator in the main square, the Jemaa el Fna, and a small crowd gathered around us. I was absolutely captivated by the experience and I could see that his audience was also spellbound. Their eyes were alive and their mouths were open in astonishment. What struck me was a sense of time travel. It was as if I had been transported back many hundreds of years, by a magic carpet.

By coincidence today I was watching some archive footage from British Pathe News which a friend had posted on Facebook. It was an old black and white film about Marrakech in 1948, because Winston Churchill went there to relax after the Second World War. In the commentary it said that if you flew to Marrakech from London you got the impression that you had fallen asleep and woken up in Biblical times – in the age of the prophets and the legends such as David and Goliath.

Well I think that is exactly how I felt both about storytelling and Marrakech generally. I remember looking for a hotel the night I first arrived with my wife. It seemed as if we were Joseph and Mary looking for an inn to stay the night. It is the same with the hlaykia. What I found amazing was that here in the 21st century were men who were communicating in the most ancient, purest and simplest way. Listening to a story is what mankind has done since the dawn of time. In North Africa it goes back to the days when nomads would pitch their tent somewhere among the sand dunes, light a fire and tell stories while looking up at the stars.

When I asked Moulay Mohamed what he thought about modern technology such as television he laughed and said that television was not the real world. He said it was a far richer experience to sit in the sunshine of the square listening to a story among a crowd, as we were doing, than on your own in a darkroom in front of a TV. I have to say that I completely agree with him.

What is it about oral storytelling that you find so attractive?

The-Last-Storytellers

What I really enjoy about the oral tradition is that it leaves everything to your imagination. It is the same with radio, which is my professional background. With radio you don’t see any pictures but they are in your head, so for example you can dream up what the beautiful princess who falls in love with the Sultan looks like or imagine the landscape of the desert. As my first boss in local radio used to tell me, “radio has the best pictures.” Conversely since film and TV feed you images, your imagination is somehow starved. I recently went to a reading aloud session in London where a writer read a short story by the Indian American novelist Jhumpa Lahiri. There was something about the listening experience that made it far more intense, interactive and alive than just reading the text passively to yourself. I kept thinking about the characters in the story for days afterwards. I don’t think I would have felt the same way from just reading it on my own. It also probably reminds us of being read aloud to by our parents so there is an element of nostalgia about it too.

Why do you think storytelling is dying out as an art form today?

In the 1970s there were eighteen hlaykia recounting their ancient tales to crowds in the Jemaa el Fna. By the time I finished working on my book (The Last Storytellers), there were only a few who were still alive and none of them were performing in the square any more. There is no doubt that young Moroccans have found television, cheap pirate DVDs of Hollywood blockbusters and social media more easily digestible and distracting than sitting down to hear a story. Sadly modern

technology seems to have killed off storytelling. One Moroccan academic said the age of storytelling died out in the 1950s when radio and then television started to invade every home.

How urgent is the need to take care of the handful of storytellers still around? These men are precious jewels. They are mankind’s heritage. If they died out completely the world would be a lot poorer. Sadly the Moroccan authorities are more interested in being modern and progressive so they do not value these storytellers as much as they should. They do not realise how precious they are. In Marrakech they say that when a storyteller dies a library burns. What I have tried to do is to save some of that vast library, before it is too late.

What do you know about the mesmerising tradition of dastangoi in Lucknow and about the people who are trying to nurse it back to life these days?

I have to confess that I do not know much about it. I gather that it is a 16th century art form that was revived in 2005. I would love to see the same thing happen in Morocco. But in many parts of the world – from as far afield as Ireland and Japan – I sense there is a revival in storytelling and a real hunger to hear stories. In France, for example, they have several hundred storytelling festivals every year. Maybe this hunger arises because humanity somehow feels it has lost its way recently.

Is it possible to compare the different ways of storytelling in different parts of the world such as Marrakech and Lucknow?

In Morocco there are ancient pre- Islamic texts that the storyteller would learn by heart and then recount everyday, sometimes for a period of several years. It would be interesting to see if some of these epics such as the Azzaliya and Antariya have similarities with the adventures of Amir Hamza. The 1,001 Nights seems to have its origins not just in the Middle East but in ancient Persia and India. What I find fascinating is that some of the stories in the Moroccan tradition also crop up in other parts of the world. An Indian colleague at work told me that one of the stories, The Red Lantern, in my book reminded him of a tale he had heard as a child. I understand that dastangoi spread eastward from Arabia towards Iran and India, with the spread of Islam. What strikes me is that this wave or migration of storytelling seems to have also travelled to Morocco but in the other direction. It would be wonderful to compare and contrast these different traditions, but I think that would require further research by folklorists and anthropologists who are far better qualified than I am.

Apart from its entertainment value why else is it important to preserve and to revive the art form of storytelling even in contemporary times?

I believe the oral tradition can offer us something that other media cannot, because it is both entertaining and at the same time educational in a very profound way. It is no coincidence that the major religions rely on stories to convey their message. Jesus understood this when he told parables, because we love stories and we never forget them. It is in our DNA. In countries like Britain, which have become largely secular, it is possible that we have lost something in terms of the moral input that these stories can teach children. Having said that children, including my own, still adore fairy stories. These have moral lessons at their heart, so I don’t think storytelling will ever die.