Martiniere Lake Anglers’ Delight

All books and no fun was never the Martinian mantra. And the lake at the college was one fun spot for angling enthusiasts as it was home to a large stock of fish, though river turtles did play game spoilers at times. Oops! the lake was also visited by a magarmuch and a gharial, courtesy the 1960 floods.

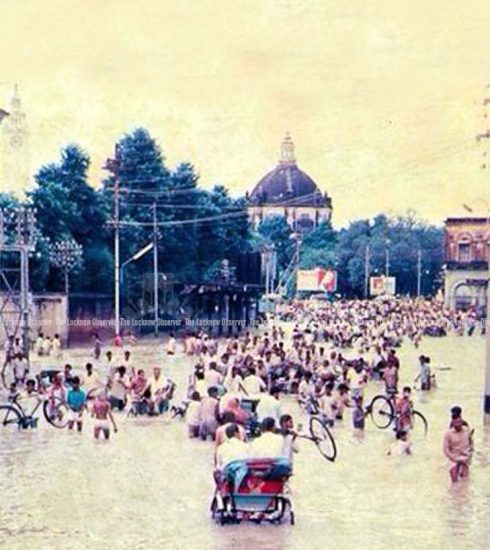

While many have admired Constantia, the venerable centrepiece of the Martiniere, few cared to look at its surroundings. Before the devastating floods of 1971, there was a largish lake created in the depression left after removal of the sail that was used to build the edifice in the late 1790s.

On a peaceful monsoon day, with rose-tinged clouds peppering the sky, the reflection of Constantia in the lake was quite a sight! The entire lake was ringed with large shady trees and at the point where part of the lake branched away towards the Gomti, there stood several tall date palm trees. Beyond the river, were ber or jujube trees and guava orchards and the typical flat alluvial landscape of rural Awadh. Till the 1960s, one could be in the countryside within a couple of miles of Hazratganj: surely unique in a medium-sized Indian city.

There were other attractions, too. The lake was regularly stocked with our main carp varieties and an angling club existed till the 1950s, supervised by Mr. Cummings, the vice-principal. Anglers had their favourite spots and permits were issued by the club to those who passed muster with Mr. Cummings.

Occasionally, after Mr. Cummings’ surveillance with binoculars from his office revealed some infraction of the angler’s code of conduct – the commonest of which was catching undersized fish – the offender’s permit was cancelled. My father was a member of the angling club from the 1940s. We, as children were permitted to tag along and catch fish with rudimentary rods. One circuit of the lake was often sufficient to catch a bagful, such was the abundance of the lake’s fish stocks.

Fishing tackle was bought in Calcutta from Kantu Brothers and their competitor Karmakar: bamboo and split cane rods with bronzed metal line guides beautifully bound with braided silk thread and fishing line made from the same silk, incredibly strong and elastic. Reels from the famous English firm Hardy and Co. had already become uncommon and were being replaced with fairly serviceable specimens from Kantu Brothers. Most of us knew how to tie hooks with gold mooga silk filament dipped in shellac. Floats were made of peacock feathers. Assorted secret recipes were used in the bait to attract fish.

One of the most successful anglers was an Italian dentist named Mandino. Assiduous attempts to obtain his recipe were made by bribing his butler. The latter reported failure because Mandino apparently burnt the packets containing the fabled bait after use.

Angling was mostly, though not exclusively, the pastime of the city’s Anglo-Indian community, its Bengali population and Muslims from the old city. After Mr. Cummings, none of the masters appeared to be interested in angling, though a few like Mr. Charles Gardner, Mr. Henry Rodrigues and Mr. Denzil D’Gama went duck shooting. The college boys, especially the boarders, though knowledgeable on natural history, collecting birds’ eggs and snake casts, also had little interest in angling. In the 1960s, the college let out the lake to a contractor from the Machhli Mohalla area, Kallu Thekedar. Kallu, a corpulent swarthy man , true to his name, came on a rickshaw to check on illegal angling, though college boys were still permitted to fish in the lake. Every year the contractor cleaned out the lake with dragnets and later restocked it. The fairly large carp which were common in the lake till the 1950s were now netted before they grew large. Among the leading poachers was a maulana from the Purana Qila area. I never saw him leave without a fish, even just after the dragnets had been used to empty the lake. I later learnt that he was a migrant from East Bengal and his success with the rod had led the nawabs of Sheesh Mahal to cancel his licence for the two tanks in Husainabad, then full of fish.

Fishing in the lake had other compensations. The sound of music from the choir and the organ in the chapel floated across the lake like a benediction. The gong rang at various intervals to mark the routine of the college. There were the brusque sounds of words-of-command as the boys marched to various duties. Occasionally the National Cadet Corps Naval Wing cadets rowed out in the brass-bound boat which was tethered at the northern end of the lake. Beyond was the shooting range, and beyond that the river. Occasionally, there came the sharp crack of .22 rifle firing from the range. The gold and blue college flag flew on Sundays from Constantia. All these constituted part of the mystery which the college held for an outsider.

The bird life of the college and its surroundings was considerable. Those who took an interest in birds told me that a pair of Laggar Falcons (Falco jugger) nested in the Lat or tower in the middle of the lake till the 1960s. A monograph by a Martiniere master in the 1890s, William Jesse, mentions the Laggars breeding on the Lat. Now Laggars are practically absent on the North Indian plains.

The rampant cutting of trees and the decimation of the lake through ‘flood control’ measures have further eroded the bird life of the Martiniere. During the 1960 floods, a small marsh crocodile or magar and a gharial or fish-eating crocodile were washed into the lake with the flood waters. They sunned themselves on the flight of steps at the base of the Lat. Attempts by college marksmen to shoot them with .22 rifles were ineffective as the bullets just bounced off the armoured hide. Later they would simply slide off the steps at any sign of danger.

Large river turtles, too, inhabited the lake and were resented by the anglers, as they drove away the fish. If hooked by accident they would release a huge spray of bubbles and getting the hook out of the turtle’s mouth was a difficult task. Sometimes we just severed the line and released the turtle.

On Saturdays during monsoons, college classes finished at quarter to two. My manservant brought lunch and a couple of rods with the requisites for an afternoon fishing. We generally sat under a tamarind tree at a spot by the lakeside near the art-room. At around six in the evening, my father came from work to pick us up and our catch. Everything, including the bicycles, were bundled into the car boot and off we went home. I cannot think of a more satisfactory end to a week of school…!

Debashish Chakravarti

Author is former diplomat who now lives in Lucknow.