Pen, Reforms, Freedom

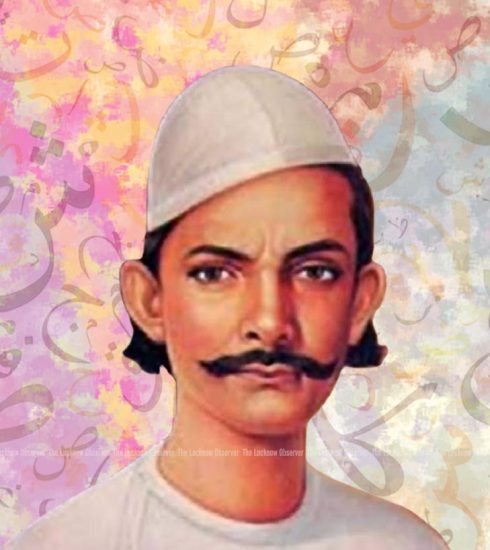

What Premchand Wanted to Bring About…

Art is not merely an imitation of reality. Though art depicts reality it is not the reality. Its merit lies in that it seems to be a reality. So says the great literary master of the realist novel in Hindi, Munshi Premchand. His writings on social issues charged with a potent humanity and stark truth made leaps in the development of the novel in our country while blessing the shelves of literature with timeless classics dipped in a stirring elixir of inspiration for life. Behind his literary ingenuity is a life of struggle and poverty, the difficult formative circumstances of a “commoner extraordinary”.

Born in the small town of Lamahi near Varanasi on 31st July 1880, he was the fourth child born to Ajaib Rai, a post office clerk and Anandi Devi. He lived in a large family. His grandfather who was the village accountant lent him the title of Dhanpat Rai Srivastava (the owner of wealth), his real name. His uncle fondly called him nawab, the root for his first pseudonym Nawab Rai, the Urdu writer’s cover, the use of which was essential to escape the censorship woes during the times of freedom.

Premchand’s particular achievement was his excellent air in both Hindi and Urdu, both branches of the Hindustani writing. He adopted the common dialect of the people, freeing his language from the strains of strictly Sanskrit or Persian influences. He learnt Urdu by the maulvi of the madarsa he attended in Lalpur with his cousins. He also learnt some Parsi there. Later in life he would stick to the job of inspecting madarsas, travelling to different places, encountering experiences and people that lent to his creative faculties and psychological understanding.

According to him– “Urdu is not the exclusive heritage either of the Muslims or the Hindus. Both have equal rights to read and write it.”

At the age of eight he lost his mother and his father remarried. He was busy constantly and Premchand was deprived of the love and attention of a parent. He enrolled in Queens’ College, Varanasi and later transferred to Central Hindu College after finishing his matriculation, unable to pay the former’s fees. His father had passed away in 1897 from a long illness. He became the sole caretaker of his stepmother and family, forced throughout his life to refrain from career choices that did not yield sufficient income even if they quenched his literary leanings and skills. He became a tutor at an early age, later a teacher in Chinar and moved between such academic jobs over different places. He was married at the age of fifteen on his family’s insistence but Premchand considered the girl pugnacious and arrogant and their marriage was always a source of dismay. After one fierce bout of quarrel with his mother, she attempted suicide. Premchand reprimanded her for the act and she left his house for her rich father’s, never to return.

Later he married a more compatible partner, Shivrani Devi, a child widow, in the face of persistent opposition from society. This girl, ostracized by society, was to later write a priceless book Premchand Ghar Mein. She was also a prominent freedom fighter. All through his student years Premchand collaborated with magazines –these were his years as the Urdu writer. And more importantly, he read. He found a job at a booksellers’ where he had ample opportunity to read from a range of different literatures, which he also translated later.

He became the headmaster of a school in Allahabad and there his literary career was launched. He began writing short stories. His first Urdu novel Azar-i-Mubaid was published in 1903 in a weekly titled Awaz-e-Khalk in episodic form. There he started writing for Zamana magazine, beginning his life long friendship with Munshi Daya Narayan Nigam, its owner. A collection of their correspondence, as invaluable letters has been recently found, opening exciting arrays of research for Premchand scholars. Premchand was a principled man and uprightness cost him several jobs. The fight for freedom also took him in. Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s radical measures inspired him. Kishna a book on women’s fetish for jewelry was published in 1907 by the Benares press club while Roothi Rani appeared in Zamana around the same time.

‘Soz e Watan’, a collection of four patriotic stories, was published in 1908. The book was banned and its copies were burned. The British, threatened by its quite protest, demanded that Premchand’s work was to be approved by the deputy officer before publishing. Till now he had donned the mask of Nawab Rai. To escape this limit, Narayan Nigam’s suggestion led to the birth of a new writer named Premchand. ‘Bade Ghar Ki Beti’ was the first story to be published under this name in December 1910.

‘Seva Sadan’, his first Hindi novel, earned him instant popularity and much longed for financial stability. From there on he continued to pour forth rich and impressive writings in Hindi– novels, dramas, short stories that have gained worldwide acclaim and have been translated extensively. He brought out a weekly magazine called ‘Hans’ from 1930.

It was his lifelong dream to start a printing press and after overriding several obstacles, he finally established the ‘Saraswati Press’. At Lamahi he built a two- storey house with his savings, which still holds testimony to his grace. He gave up his government job during the Swadeshi Movement inspired by Gandhiji’s philosophy, even though for him it meant a constant struggle for livelihood to sustain a large family. All the while his health deteriorated. In 1936 he was nominated as the President of the Progressive Writer’s Association in Lucknow. The same year he passed away, leaving behind an unparalleled literary legacy.

Several privileged places had the fortune to be associated with this great poet. He even taught at a Gorakhpur college. In Lucknow he was associated with a magazine called ‘Madhuri’. His residence here still stands in Golaganj area. In his famous story ‘Shatranj Ke Khiladi’, which was later adapted as a lm by Satyajit Ray, he comments on the nineteenth century state of Awadh, the elite’s detachment towards the agony of lower classes. He begins: “It was the time of Wajid Ali Shah; Lucknow was sunk in luxurious idleness…so as to what was happening in the world, no one knew or cared.”

One surprising element of Premchand’s career was his spree as a scriptwriter in Mumbai. He wrote the script for ‘Mazdoor”, a film that caused great uproar and inspired labourers to fight for their rights. He also featured as a union leader in the film. Ironically this was also the film that inspired workers at his press to strike. The shortage in means had denied them their monthly salary. Premchand was disenchanted with the commercial, non-literary atmosphere of the film industry and despite demand, left the city after the completion of his one-year contract.

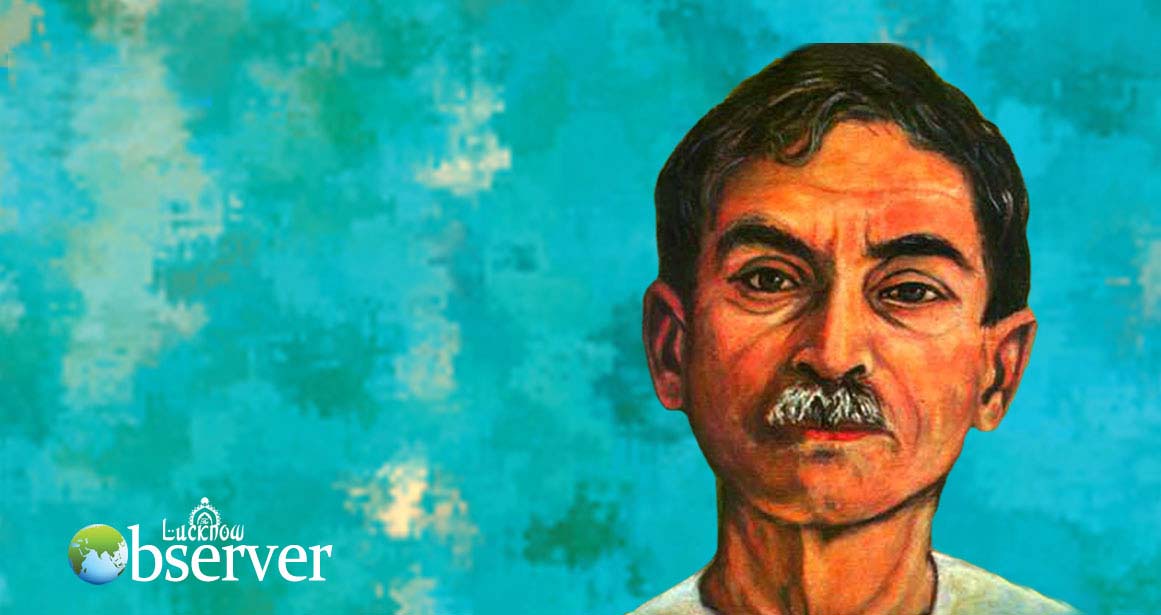

Premchand brought powerful social realism to Hindi literature depicting the Indian masses and their beliefs, practices and reality. He was a reformist and by his novels, he sought to steer the nation to a better recourse. Dowry, colonialism, women empowerment, the zamindari system were lent in the compelling web of fiction writing and released. He evinced an insight of human psychology and complexity of emotions that is amazing. His knowledge and comprehension of the driving issues of his times was absolute and lent the writing its energy and forceful conviction.

His voice was contemporary, modern, unique and it was the voice of a common man who had seen the best and worst of life just as others. This bond with reality, difficulties, lent the colour of truthful beauty to his writings and made them come alive. Pathos ruled his work and morals reigned supreme.

“Kavita Sacchi Bhavnao Ka Chitra Hai Aur… Sacchi Bhavnaye Chahe Ve Dukh Ki Ho Ya Sukh Ki Usi Samay Sampann Hoti Hai Jab Hum Dukh Ya Sukh Ka Anubhav Karte Hain…”

‘Godan’, his most celebrated novel, tells the story of a poor farmer Hori, who longs to own a cow. In ‘Gaban’ the protagonist is out to impress his newlywed wife and empathy directs its narration. His other prominent works include Maidan-e-Amal, Karmbhoomi, Nirmala, Manorama, Premaashram, Varadaan, Rang Bhoomi and many more.

All his characters are picked from the quintessential Indian societal fabric and they are impactful, genuine people whose concerns were the concerns of the Indian masses during the struggle for Independence. His writing was his weapon against the atrocious British rule. In the end he aims to reaffirm people’s faith in humanity. Their simplicity and belief in good and evil, providence are his entire intent.

It’s this inimitable voice with its immense depth of understanding that has lit literature annals with its brilliance. For a bite of his magnificent prose in the month of Ramzan here’s the opening from his oft repeated and celebrated short story Eidgah that has found a place in moral teaching books and replicated in other forms-

Ramzan ke pure Tees rozon ke baad eid aayi hai. Kitna manohar, kitna suhavna prabhav hai. Vrikshon par ajeeb haryali hai, kheton mein kuch ajeeb raunak hai, aasaman par kuch ajeeb laalima hai. Aaj ka surya dekho kitna pyara, kitna sheetal hai, yaani sansar ko eid ki badhai de raha hai. Gaon mein kitni hulchal hai. Eidgah Jane ki taiyari ho rahi hain. Kisi ke kurte mein button nahi hai, padosi ke ghar mein sui dhaga lene daude ja raha hai. Kisi ke joote kade ho gaye hain, unme tel dalne ke lie teli ke ghar pe bhaga jata hai. Jaldi jaldi bailon ko saani pani de denn. Eidgah se lautate lautate dopahar ho jaegi. Teen kos ka paidal rasta aur fir saikdon logon se milna bhetna, dopahar ke pahle lautna asambhav hai. Ladke sabse zyada prasann hain. Kisi ne ek roza rakha hai, wo bhi dopahar tak, kisi ne wo bhi nahi, par Eidgah Jane ki khushi unke hisse ki chiz hai. Roze bade-budhon ke lie honge, inke lie to eid hai…

Nikita Gupta

Writer is a student and her passion is painting

(Published in The Lucknow Observer, Volume 2 Issue 16, Dated 05 July 2015)