The Prince of Print

Munshi Newal Kishore is often called the William Caxton of Lucknow after the English businessman who first introduced a printing press in England in the 15th century.

The city may have reduced his name to a road today but in 19th century Lucknow, Munshi Newal Kishore was the prince of print.

Munshi was the prince of print because the press that he founded in 1858 in Lucknow was the first of its kind in North India. From a single Indian made hand press, Munshi’s business expanded into an industrial empire. This allowed him to buy the latest technology from abroad and to earn much influence and prestige which he used to preserve the region’s literary heritage.

The young publisher and founder of the largest privately owned printing firm soon became part of the city’s exclusive circle of urban elite and he continued to make generous contributions to modern as well as traditional education. His patronage and philanthropy towards institutions of Urdu culture is enough not to forget Munshi even more than hundred years after his death at the age of 59 years, in 1895.

After the end of Lucknow’s monarchy and annexation of Avadh by the British, scholars had lamented the dearth of textbooks in Arabic and Persian. Recalls Manazir Ahsan Gilani, teacher Darul Ulum, one of Avadh’s most prestigious institutions of Islamic learning at Deoband that for a long time it was books donated by this one non Muslim had helped teachers and students at the Darul Ulum to fulfil their religious and scholarly requirements, to understand the Quran and solve the linguistic problems of Hadith.

Lav Bhargava, a descendant living in the same house built by his amazing ancestor in 1870 in the heart of Hazratgunj feels that he has inherited Munshi’s life long appreciation of the culture and language of others. Lav is attracted to politics precisely because it gives him a platform to share the benefits of communal harmony with the public and to continue the dialogue about the very inclusive, tolerant and composite Ganga Jamuna way of life.

Once upon a time the now defunct Newal Kishore Press (NKP) was indeed a turning point in the history of publications in Lucknow for more reasons than one. The press allowed Munshi to flag off a cultural renaissance and a revival of interest in literature in local languages at a time when people were deeply disappointed with politics.

“As the first Indian to newly open a press in post-Mutiny Lucknow, he heralded a new era of the mass-produced book. He not only set printing in Arabic, Persian and Urdu on a sound commercial footing but also established himself as the city’s first publisher of Hindi and Sanskrit books,” writes Ulrike Stark, author An Empire of Books: The Newal Kishore Press and the Diffusion of the Printed Word in Colonial India.

Abdul Halim Sharar, Munshi’s contemporary and great Urdu essayist and cultural historian wrote that the NKP was opened after the monarchy collapsed in Lucknow and ran on such sound commercial lines that it could produce Persian and Arabic books in great bulk which no other press had the courage to attempt.

“Eventually the press gained such pre eminence that it revived all eastern literatures and Lucknow acquired great distinction in this field. Lucknow benefitted in that it was able to meet all the literary demands of Central Asia including those of Kashgar, Bukhara, Afghanistan and Persia,” continues Sharar who was employed by Munshi around 1880 as Avadh Akhbar’s assistant editor at a monthly salary of Rs 30.

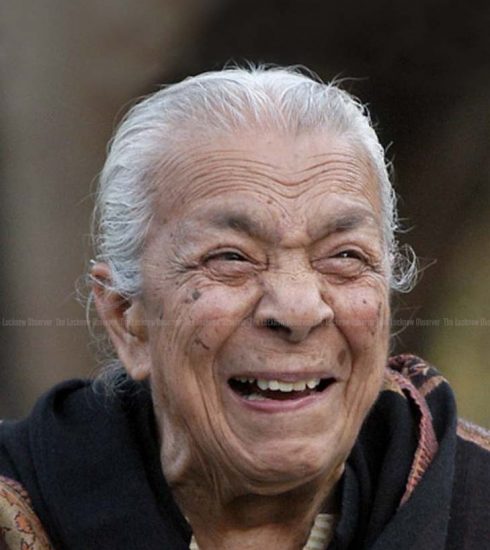

Munshi was 22 years old when he came to Lucknow in 1858. He was well built and handsome. His natural good looks were further enhanced by his elegant attire in Lakhnavi style. When the Delhi based Mirza Ghalib first met Munshi he was inspired to describe him in verse. Said Ghalib of the young man that the creator had bestowed upon Munshi the beauty of Venus and the qualities of Jupiter.

“He is himself the conjunction of two auspicious stars,” raved Ghalib who wrote to a friend that when the NKP prints a man’s writing, it raises him to heaven. “The calligraphy is so good that every word shines radiant! May Delhi and its water and its press be accursed,” added Ghalib.

Sir Robert Montogomery, chief commissioner of Avadh and Colonel Saunders A.Abbott, commissioner and superintendent, Lucknow invited Munshi to the city in late 1858.

“These gentlemen extended, in consideration of my loyalty and of what I had done in the Punjab for the British Government, their patronage to my newly- established Press and favoured me with the printing of all English and Vernacular documents connect with their Establis- hments,” writes Munshi.

Like most 19th century publishing houses, the NKP printed and marketed books and in early 1859 also launched Avadh Akhbar, a newspaper in Urdu. This was a great moment for Urdu that had already replaced Persian as the official language in 1837.

Munshi made a huge commercial success of the NKP and spread the magic of the written word amongst ordinary citizens with the publication of Avadh Akhbar that became very popular with the Urdu reading public.

At a time when most Urdu papers were short-lived, Avadh Akhbar remained in circulation till 1950. At first it had appeared each Wednesday and during the following years successfully competed against the rapidly growing number of Urdu papers. From four pages its size was soon increased to sixteen pages and from a weekly it became the leading Urdu daily of North India after 1877. The growing popularity of the paper did much to enhance the spread of the newspaper reading habit among the aristocracy and educated middle class in the North Western Provinces and Avadh.

From a visitor to Lucknow, Munshi soon became one of the city’s first citizens. The influence he wielded in local society as entrepreneur and publicist over the years allowed him to exchange his initial home in the old city for real estate in the prime location of Hazratgunj, closer to the British seat of power.

Born in western UP, Munshi was taught at home and at an Islamic school. He did not complete his higher education at Agra College. He went to Lahore to work in Harsukh Rai’s famous Koh-e-Nur press instead on a monthly salary of Rs 15.

There he watched how a Urdu newspaper by the same name was edited and printed. Koh-e-Nurwas first published in 1850, a few months after the British had annexed Punjab. The paper marks the beginning of serious Urdu journalism in the province and was popular with the native elite, enjoying the patronage of the rulers of Kashmir and Patiala. The British authorities first noticed Munshi’s business and literary acumen in Lahore and later offered to give him permission to publish from Lucknow.

During his time at the Koh-e-Nur Press, Munshi became familiar with various aspects of printing, publishing and newspaper editing. It is here that he received the title of Munshi due to his love for reading and writing. After a brief return to Agra to start his own newspaper, Munshi was again hired to edit Koh-e-Nur throughout the difficult period of mutiny by Indians against the British. In Munshi the British saw a loyal supporter of colonial rule. At this time , the British were angry and most insecure after the bloody revolt against them by local people in 1857. But Munshi had won the trust of the authorities which led to the invite to Lucknow, capital city of India’s heartland.

Lucknow had lagged behind in Urdu journalism at this time. This was due to the temporary closure of all printing presses and strict censorship that had prevailed in Avadh. After the annexation of Avadh by the British at least seven Urdu weeklies were launched in Lucknow within a year’s time.

However the 1857 revolt had brought the city’s thriving print and publishing industry to a complete standstill. By the time Munshi came to Lucknow there was no local competition in the newspaper trade. It was comparatively easy for Munshi to open his press and his work eventually inspired him to make education his mission and a lifelong concern.

Munshi’s success in Lucknow is attributed to a number of factors like British patronage in the form of subscriptions and overall support to the NKP. Munshi began his business after a friendly nod by the colonial administration. He won the rights to print all kinds of government forms and registers. He held a monopoly in textbook printing in Avadh and managed to get the lion’s share of official patronage in the combined North Western Provinces and Avadh. He managed the press professionally and the paper partly financed itself through advertisements. Besides eminent scholars, poets and prose writers were hired as editors of Avadh Akhbar who had engaged in literary debate with many local readers of one of North India’s most influential and widely read Urdu newspaper in 19th century colonial India.

The premises of the Avadh Akhbar were not just an editorial office but were a meeting place of very hectic literary activity, involving members of Urdu literati like Ratan Nath Sarshar, Mirza Hadi Ruswa, author of Umrao Jan Ada and ordinary readers.

This is what makes Munshi’s reputation shine to this day as an intellectual mirror responsible for reflecting the very vibrant Ganga Jamuni tehzeeb or composite culture of Avadh in all its glory. And inspiring contemporary citizens of the city to do the same.

The Man

Munshi Newal Kishore was raised in an orthodox Hindu family from western Uttar Pradesh that traces its earlier home somewhere in Gurgaon, Haryana. Munshi was taught at home and as a child probably enrolled in the village primary school where he learnt to read and to write in Persian, Urdu and perhaps Arabic. At the Oriental Department of Agra College he later learnt more Persian, and English. It is at Agra College that Munshi is said to have developed a love for literature and journalism although he never graduated from the college.

At the age of 14 years Munshi was married to Saraswati Devi from a family of wealthy landlords. Three daughters and a son were born to them but only two daughters survived. Munshi adopted Prag Narayan, a nephew as heir and who was brought up not by Saraswati Devi but Munshi’s Muslim wife known as Begum Sahib.

The Publisher

Munshi, a Hindu made his mark in the history of Quran publishing. He was presumably the world’s first publisher to issue a finely lithographed Quran at the sensational price of one rupee and eight annas in 1868. This was the first time that the Quran was available to ordinary readers, inviting Muslims of even moderate means to own their own copy of the Quran.

Stories are still told of how Munshi had required all daftari workers to perform the vuzu, or ablutions before starting their work on binding the Quran.

Why Lucknow

Munshi Newal Kishore is often called the William Caxton of Lucknow after the English businessman who first introduced a printing press in England in the 15th century.

Munshi was not from Lucknow. He came here with nothing except high spirits. He started his print business in 1858 when there was no competition in Lucknow. After the bloody events of 1857, most of the earlier presses of the city were destroyed or forced to close down. Real estate and housing was cheap and Lucknow was a treasure house of highly skilled artisans, scholars and men of literature who were without a job in a city that had become politically important as the new capital and administrative centre of Avadh.

Printing technology had already made its way to Avadh around 1817 when Nawab Ghaziuddin Haidar founded Lucknow’s first typographic press, the Matba-e Sultani or royal press. But a local print culture was established only in 1830 with the arrival of lithography when the Anglophile King Nasiruddin Haidar invited Henry Archer of the Asiatic Lithographic Press to shift his business from Kanpur to Lucknow.

As the printing business flourished, the demand for paper too increased. Munshi the visionary immediately established the first paper mill in Avadh. Set up in 1879, the Lucknow Paper Mills began operation in 1880 on the banks of the Gomti as imported machinery and paper from Bengal came into the city by ship. Munshi was the paper mill’s largest proprietor and he further strengthened his position in the management by marrying Prag Narayan, his adopted son and heir, to the daughter of one of the mill’s high officials.

Famous Titles

The four great figures in the world of 19th century Urdu novel are Nazir Ahmad, Ratan Nath Sarshar, Abdul Halim Sharar and Mirza Hadi Rusva who were all connected to the the NKP. Nazir’s masterpiece Mirat al-arus was published by NKP. Translator and editor Sarshar’s Fasana-e Azad was serialised in Avadh Akhbar to wide popular acclaim. Sharar was on the paper’s editorial board and in 1889 NKP published Ruswa’s immortal tale of Lucknow courtesan Umrao Jan Ada.

Munshi once had in his possession the collected poetry of over 50 Urdu poets including contemporaries like Ghalib, Bahadur Shah Zafar and Abdul Ghafur Khan ‘Nassakh’ and owned copyrights of minor poets Amir, Wasti and Ashiq.

Avadh Akhbar

Avadh Akhbar, the very popular Urdu daily did much to spread the habit of newspaper reading among the urban and rural gentry and the educated middle class in Avadh. Its aim was to inform and to educate the Indian public. At the same time its literary contents promoted poetry and prose writing, literary events, new publications and provided a platform for discussions to the Urdu literati.

Wrote an enthusiastic reader in 1870: Munshi Sahib your paper is a fountainhead of eloquence and a source of enchantment. Who am I to praise it, big words from a little mouth. Judging from the multitude of news and the acceptance on the part of our contemporaries one could rightly call it the mother of newspapers…

Eminent Editors

Munshi worked with many eminent scholars, poets and prose writers of the day. This made Avadh Akhbar even more influential in the promotion of modern Urdu literature.

Well known Farangi Mahal scholar Mufti Fakhruddin Ahmad Fakhr Lakhnavi was an editor like Maulvi Raunaq Ali. The most famous editor was Ratan Nath Sarshar whose Fasana-e Azad was published in installments that had sky rocketed the circulation of Avadh Akhbar. Abdul Halim Sharar great Urdu essayist was on the editorial board of the newspaper and wrote regularly for it. The best known outside contributor was Ghalib who submitted articles on a number of of topical themes among them a piece on the Afghanistan war in 1862. Ghalib was a regular reader ofAvadh Akhbar and was mailed a copy to Delhi where he had lived. In a letter to Munshi the legendary poet promised to forward a few recently composed Persian ghazals in 1860. In December 1863 Munshi met Ghalib and had impressed the elderly poet with his good looks and agreeable manners.

Avadh Akhbar had a foreign correspondent in London as well and one of its regular contributors was eminent orientalist scholar and linguist Edward Henry Palmer who was fluent in Arabic, Persian and had studied Urdu at London’s University College.

Much after Munshi’s death in 1895, Prem Chand declined to edit Avadh Akhbar in 1914 but in 1927, the inimitable short story writer was appointed editor of Madhuri, a Hindi literary magazine launched by NKP in 1922.