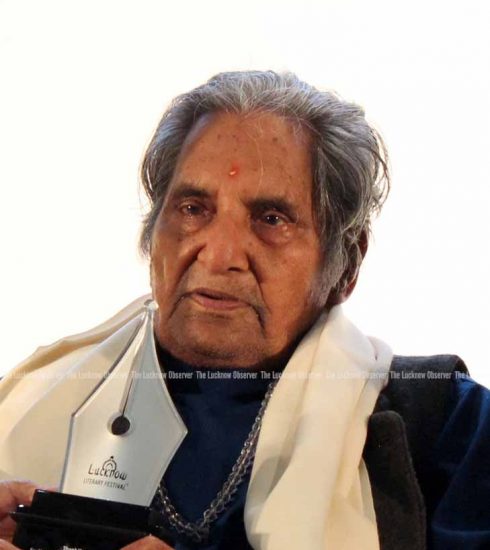

Pride of Lucknow Award

Setting the record straight

Veena Talwar Oldenburg, author of Dowry Murder: Reinvestigating a Cultural Whodunit, The Making of Colonial Lucknow and Life Style as Resistance: The Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow is first and foremost a blue blooded Lucknowite.

A post graduate inEuropean History from the University of Lucknow and winner of two gold medals, Veena left Lucknow for the United States in 1970. Recently, Veena was honoured in the city with the Pride of Lucknow Award at the second edition of the Lucknow Literary Festival hosted here by Lucknow Society.

Today, an avid New Yorker, Veena needs little excuse to visit Lucknow. Her present day research is on Gurgaon which makes it easier for her to travel to Lucknow a little more frequently than from New York.

As a scholar Veena’s work is most precious for recording history as told by local people and Indian academics and not only from the point of view of colonialists and British historians. Throughout her scholarly life, Veena has been trying to set the record straight.

She is still looking at the role of the East India Company and how the British snatched for themselves sovereign states by first spreading disgraceful rumours about the rulers. She gets livid when Wajid Ali Shah, the last ruler of Lucknow is called a debauch. Her first work, The Making of Colonial Lucknow outlines colonial urban policy in the capital of the Northern Provinces, keeping in mind the after effects of the 1857 mutiny and the need for cleanliness, safety and security for the British population in the city.

Recalling her childhood in Lucknow, Veena says that those days, so soon after the partition of the Indian sub continent, were peculiar. Many relatives from her maternal side were from Punjab, some of whom had experienced murder and mayhem on the border between India and Pakistan. She overheard stories like somebody managed to save a necklace and was able to buy a house with it in Lucknow.

In Dowry Murder: The Imperial Origins of a Cultural Crime, Veena’s version of the dowry system in India is an eye opener. She gives a historical account of colonial conditions that shape modern understandings of dowry murder in India. Blending together colonial reports with her observations of activists and their work at the women’s organization Saheli, Veena argues that colonialism corrupted the institution of dowry.

The demands made by the groom from the bride at the time of marriage, is not dowry. For dowry used to be voluntary gifts given by the bride’s parents, kin and sometimes by the whole village at the time of marriage, says Veena. The bonhomie and exchange of gifts was reciprocal but the British introduced a masculine economy to diminish the control of women over economic matters.

Laws introduced by the British caused economic upheaval and transformed what was till then a safety net for women, into crime. During her research, she found nothing in the Vedas, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the shastras, that says kill your wife if she does not bring you dowry. She defines culture as something dynamic that changes and reinvents itself due to social and economic pressures. There were so many pressures on Indian society during the colonial period that changed many aspects of life here. She defines the colonial period as a time when the Europeans seemed to help Indian women. But her research concludes that the situation of women in society worsened under the

British. She talks of collusion between Indian patriarchy and colonial patriarchy that deprived women of their rights.

The cultural historian who is well traveled says that crimes against women are committed around the world. They may not be called dowry deaths but women are burnt alive in American society too. These are murders and not crimes specific to Indian society. She says that no history of India is complete without recognizing the connection between gender, and the political economy. To find out more, that is what she continues to research and to write so that readers get as objective a picture of the past as it is for a historian of present.